|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Walking Tour Stop 9

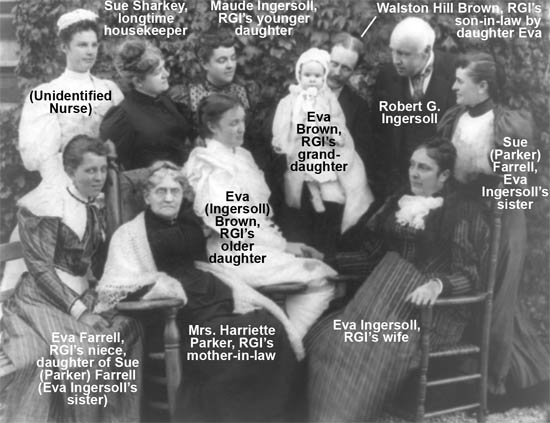

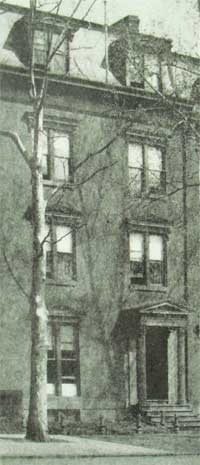

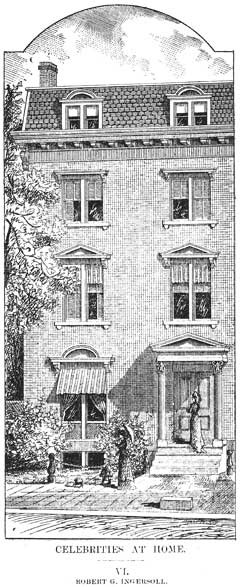

Ingersoll’s first home at 25 Lafayette Square, near the N.E. corner of Lafayette Square (not extant) The original address of Ingersoll’s house was 25 Lafayette Square. It was torn down in 1903 to make way for the present unnumbered 5-story, light-brown brick building. This building occupies also the site of the neighboring house which stood at 23 Lafayette Square. A plaque points to a former occupant, the Cosmos Club. It is now part of the National Courts building. Ingersoll’s home was described as “a large brick house with heavy brownstone trimmings, generous halls and big square rooms. It was diagonally across from the White House. Next door was the old Dolly Madison house, and a few steps away stood the Seward mansion” (Cramer, 1952, p. 180). A photograph of the Ingersoll House in the Photo Collection of the Library of Congress shows a townhouse with three stories, topped by a fourth with dormer windows. Two large windows faced Lafayette Square on each floor, except the first where the single window was paired with the front door. Five steps led up to this door, which was flanked by two round columns and a porch in the classical style. The Ingersoll House had been built in what had been the garden of the Dolly Madison House. This yellow house on the corner of H Street and Madison Place, with the wrought-iron balcony was the home of the President’s widow from 1837 to 1849, as its plaque indicates. The next house, with the wrought-iron balcony, at what was 21 Lafayette Square, is the Benjamin Ogle Tayloe House. Its plaque indicates that it was also known as “The Little White House” when Mark Hanna occupied it during the administration of President McKinley. Next door, at 17 Lafayette Square, stood the Rodgers-Seward House, whose site is occupied today by the National Court Building/U.S. Court of Claims (designated 717 Madison Place). In 1845, this house was the temporary home of President James K. Polk and his family while the White House was being renovated. It was occupied during the Civil War by Secretary of State William Seward, who was attacked by one of the Lincoln conspirators. When Ingersoll was in Washington, it was the home of Senator James G. Blaine, whom Ingersoll had nominated for President at the 1876 Republican National Convention in his famous “plumed knight” speech. What was the courtyard of the Ingersoll House may be reached by walking through the gate leading to the National Court Building at 717 Madison Place. Once inside the courtyard, proceed to the left until you reach a patio with tables. A large, golden eagle is attached to the wall of the building that now occupies the site of the Ingersoll House. The Ingersoll home comprised a large household. The census of 1880 lists twelve occupants of the house! These were:

At the entrance to the parlor was a bust of Shakespeare. On the head of the bust could be seen Ingersoll’s hat at a rakish angle. In the summer, the hat was a white Panama; in other seasons, it was a black derby or a topper. Above the fireplace hung a portrait of Ebon Clark and next to the mantle was a bust of Ingersoll. In a bow recess stood a 3-foot cast of the Venus of Milo. A nearby Steinway Grand was played regularly at the weekly socials. In the library could be seen a profusion of art objects and family scenes. On one wall hung a portrait of Beethoven, and there were busts of Voltaire, Newton and Paine. “Lining the four walls, halfway from the floor to the ceiling, were shelves of books.” On a center table “was a massive book in heavy morocco binding edged with gilt, the complete works of Shakespeare” (Larson, 1962, pp. 185-186). Ingersoll called it his bible. A Washington journalist writing under the name of Ruhamah described Ingersoll’s home as follows in his “Washington Gossip” column: This prince of pagans occupies a handsome residence on Lafayette Square. On Sunday evenings the Ingersoll home is open to their friends, and these Sabbath symposiums are most enjoyable of all the weekly round of social affairs that any season can offer. Ease and hospitality liven the air from the square tiled hall into which the vestibule opens to the remotest sanctum. Before the church bells have ceased tolling the faithful to the evening service people begin dropping into this charming home and the smooth face and round head of the host appears to the visitor in the hall with unhackneyed and cordial greetings. Adding to his own social attractiveness Colonel Ingersoll has a delightful family to make it more inviting to his guests .... The house is admirably fitted for entertaining, with its three rooms opening into one another and the dining room beyond. The first parlor has crimson hangings, dull red walls and a dark Turkey carpet, with deep velvet furniture. The second parlor is in light colors, with cream walls, pearl-tinted carpet and a large book case where the works of Spinoza and Mark Twain stand jocularly side by side, and Matthew Arnold, agricultural reports and Max Muller lean together. The third room contains the piano and more books, while the walls all through are hung with paintings and fine engravings. For wit, eloquence and repartee Colonel Ingersoll finds no superior, and with a room full of friends about him his bon mots and epigrams are incessant. In their home on Lafayette Square, the Ingersolls received ambassadors, diplomats, members of Congress, department heads, judges, writers, actors, musicians and notables like Frederick Douglass and Clara Barton. The Ingersoll biographer Herman E. Kittredge wrote (Kittredge, 1911, pp. 435-436): Thus in Washington, of a Sunday evening ... men of national and international reputation — prominent members of the House and of the Senate, members of the Cabinet, etc. invariably formed part of the circle of which the great orator was the magnetic center. During “presidential years,” it was not unusual to find in the Ingersoll drawing-room a half-dozen prospective candidates for the presidency, absorbed in the discussion of current political questions. But it must be noted that Ingersoll received not only the famous and well heeled; he never ignored the poor and unfortunate who called upon him. Another Washington correspondent wrote as follows about Ingersoll: It is hard to write about the colonel and not indulge in what would seem to strangers to be extravagant praise. He is such a loyal-hearted gentleman, that one’s admiration for his moral qualities are apt to dim the appreciation of his brilliant intellectual qualifications. No cabinet officer was ever more pursued by place hunters than the colonel by the public. The callers come before breakfast and besiege the house until nearly midnight. Everyone who comes gains admittance. The poor and the humble sometimes fare better than the rich and prosperous. One woman came to convert Ingersoll, wrote the correspondent. He invited her for dinner. After several visits, she told him, “I apologize. I do not care what you believe. You are leading more of a Christian life than I ever hope to accomplish.” Ingersoll had moved to Washington because it offered his law practice the larger field of federal litigation. He also thought that he could exert political influence here and gain an influential position for himself. While he did exert some political influence from his home in Lafayette Square, President Rutherford Hayes was too fearful of the opinions of the religious to offer him an office. The cold shoulder he received was expressed in this contemporary song (Blanchard, 1910, p.178): Ingersoll, Ingersoll, he’s the man for me. Several times in 1879, Ingersoll visited President Hayes in the nearby White House seeking a presidential pardon for D. M. Bennett. The publisher of The Truth Seeker had fallen victim to the quasi-governmental Society for the Suppression of Vice headed by Anthony Comstock for sending allegedly pornographic material through the mails. Ingersoll was, however, unsuccessful in persuading Hayes to pardon Bennett. As mentioned, Ingersoll campaigned for Garfield in 1880, and he did so most energetically. After Garfield was elected, the Garfield-Arthur Club of Washington, preceded by a section of the Marine Band, paraded on November 5 through the streets for half an hour. It ended “with a celebration and serenade at the brightly lighted and decorated home of the Ingersolls.” He came out and made a little speech, “that he had heard it said that the Democratic party had gone to a place that he did not believe in (long and continuous applause) but for the sake of argument if there was such a place and its tenant was the Democratic party all he could say was that he pitied the place” (Smith, 1990, p. 178). In the interval between election and inauguration Garfield met often in Washington with his designated-Secretary of State Blaine. Since Ingersoll and Blaine were neighbors, Garfield frequently ran into Ingersoll at the Blaine residence (17 Lafayette Square). It may be conjectured that if Ingersoll had requested a post in his administration Garfield would have complied. “But Ingersoll had good reason for not seeking an appointment in the government. It undoubtedly would have to be of cabinet or high diplomatic rank and might not survive a debate in the Senate. Besides, the constraints of public office were incompatible with his irreversible career in freethought” (Smith, 1990, pp. 180-181). “Splendidly endowed as he was he could have won great distinction in the field of politics had he so chosen,” concluded a reporter for the Chicago Tribune after Ingersoll’s death. “But he was determined to enlighten the world concerning the ‘Mistakes of Moses.’ That threw him out of the race” (July 22, 1899). On June 28, 1881, Ingersoll consulted with Garfield at the White House concerning the Star Route trial in which Ingersoll was defending Senator Dorsey. “On July second Ingersoll spent the evening from eight to ten in conference with Garfield. In the morning, when they were to resume discussion, Ingersoll was late, driving up at the White House just in time to greet the president on his way to the trains to keep an out-of-town engagement. Ingersoll returned home. Some fifteen minutes later there were cries in the street: ‘The President has been shot! The President has been shot!’ Hurrying to the depot Ingersoll was admitted to the upstairs room where the wounded president lay stretched out on the floor. Garfield recognized Ingersoll, they exchanged a few words, and Ingersoll returned home” (Smith, 1990, pp. 182-183). On January 8, 1882, Ingersoll delivered the oration, “At a Child’s Grave,” at the funeral of Harry Miller in the Congressional Cemetery, 1801 E Street, S.E. He was the little son of Ingersoll’s freethinking friend Washington Police Detective George O. Miller, who lived at 1915 Vermont Avenue, N.W. Addressing preachers of hell fire, Ingersoll said, “No man, standing where the horizon of a life has touched a grave, has any right to prophesy a future filled with pain and tears.” On January 14, 1883, as chairman of a lecture on Lincoln the lawyer, he stated his preference for direct experience of life as a better source of education than the colleges that Lincoln and he had not attended, “where brickbats are polished and diamonds dimmed” (Washington National Republican). On February 13, 1883, the Ingersolls celebrated their 21st wedding anniversary at their home in Lafayette Square amidst some 500 guests.

|

|

© 2011 WASH, Washington Area Secular Humanists. All rights reserved.

|